About the author: Alex is a Q-grader with 10 years of coffee industry experience, and co-founder and coffee buyer/roaster for Scenery

I was extremely lucky, for my own development, that that cafe in which I really learned to taste had high and exacting standards - for everything - such as the tasting notes I was exposed to were pretty accurate. But the more I worked in the industry, the more I tried coffees - in every stage of their life, the more I understood how it worked behind the scenes - the less satisfied I was with the result.

So I want to talk about my understanding and experience of how tasting notes are set by a roastery. And this is by no means an exhaustive view on the process, but one that should be more broadly descriptive of how a lot of roasteries will do it. And I feel It'll be very happy to update & retract if someone was trying to say it's absolutely wrong, and there are definitely exceptions

So first of all, what are coffee tasting notes? I would say it’s a common language to be able to first accurately say, is, does it taste good to us, yes or no? If so, does it remind us anything (because after all, flavour notes are mostly sensory memory, something we’re actually terrible at as a species), and then do you have a shared common, gestalt perception with other people about what that flavour actually represents?

The two tiers of tasting notes

It’s where a lot of the quality based value for speciality coffee resides - the communication of flavour. So what are the tasting notes on bags? Up on the menu at a coffee shop? I propose there are really two tiers of tasting notes.

The first is the tasting notes that you yourself perceive?

Which starts from the most basic - Does it taste good,or taste bad? No other qualifiers needed - good or bad still counts as a note. Which can then be extended on a spectrum all the way out to tasting some really specific and nostalgic flavours on the good side, or something that's really disgusting on the bad. So the first tier - personal perceived taste.

And then we have the second tier - what I am going to call marketing taste notes.

You know, ultimately this is tasting notes as a form of selling you something - shouting about the quality based value, and it could be on a bag of coffee, it could be a roastery website. It could be on the menu of a coffee shop. It could be even a friend trying to encourage you to try a coffee they brewed and they think it’s really nice.

"This carbonic macerated Geisha immediately impresses with its amber clarity and ethereal aromas rich in bergamot, rose petals, and wild honeycomb. The palate reveals a dance of passionfruit and white peach, underscored by hints of lavender and candied Meyer lemon peel. Its silky body is reminiscent of a finely aerated wine, concluding with a resonant finish of golden raisin and a touch of cacao nib."

An example of the author's point - AI generated, but at the extreme end of things. This coffee does not exist - but it sounds great, right?

It's all in the case of encouraging you to buy in first and foremost, then secondly enjoy it. So the crux of this article - where do we define where those flavours come from? Because they are different from personal perceived taste. I will explain why, and in the process, let’s go on a little journey about how coffee is bought.

The journey from tree to tasting note:

Let's start back at the trees that coffee came from. When the trees are growing and the coffee is ripening and you know, the hard work of agronomy & agriculture is ongoing, Now we might have some idea of how the final product might taste from the varieties, the farm location, previous harvests.

But we don’t have tasting notes yet.

Harvest: Picking? No idea yet, might be good if it’s mostly ripe fruit…

Processing: Again, we might have some clues as to potentially where we think it's going, but we don't know yet.

Drying: Aha! now we might take the earliest, possible samples. From the drying beds a sample will be taken to hand mill (removing the protective outer layer to the roastable green seed form) a sample and we’ll take them to a lab (the local co-op, exporter, importer or in some cases sent directly to the roastery) and someone will roast them, and they’ll cup them, which is a form of controlled brewing.

Image: Hand milling coffee samples in the Sucafina lab, Ethiopia

That's good for establishing quality levels, comparative tasting, even finding some tasting notes.

But the coffee is really fresh - and just like roasted coffee, green coffee goes through an arc of quality. Too fresh is the same either way - it doesn’t taste as good as it will with a little bit of rest. After a while it opens up, reaches a peak of flavour, and eventually starts to get stale. Unlike roasted coffee, this process typically happens over a course of months with green coffee, up to a year* (*this has so many caveats that it’s worth an entire post of its own)

So, we taste the coffee for the first time, at the earliest possible point - is this what goes on the bag? Because this coffee is going to change after its “reposado” (rest). And we’re trying a little sample roast, not a full batch on a production roaster - so that will change the perceived flavour expression as well.

And say that coffee is selected for import - it gets sent to a dry mill, removing the full protective layer (cherry husk for naturals, parchment for everything else). It’s sorted for defects, density - the quality might improve, likely still fresh though. You get sent a “pre-shipment sample (PSS)”

The lab at La Central de Cafe / Primavera Coffee, Guatemala City

To confirm the quality before shipment, post milling, and to approve the logistics.

So another sample roasted look at the flavour - is this where the tasting notes should come from?

But of course that coffee is going into a container, at the whims of the shipping companies. Could turn up in 3-4 weeks - could be 3-6 months if you get unlucky with transhipments and paperwork. Spending 6 months bouncing from tropical port to tropical port on the high seas never tends to do wonders to a coffee’s quality…

So eventually it arrives at the warehouse in the UK - maybe it arrived on time, maybe it didn’t. The dutiful staff at the warehouse take samples from across the container to send for quality control - comparing PSS with arrival. Maybe that goes to the importer or yourself directly, depending on how much of that container of coffee (275 x 69-70kg sacks, or 320 x 60kg sacks, for a 20ft standard container) belongs to you.

So we’re getting close now, maybe a bit closer to representative - another sample roast, another cupping. Are those notes going on the bag? Maybe someone will brew the coffee in the lab - from a sample roast - and share it around. Roasters aren’t often the best brewers anymore, and a sample roast is not a production roast - they are optimised for cupping. But it happens, and some notes are shared, if there are multiple people tasting - looking for the common threads. Sometimes it might just be a head roaster or head of coffee, in any case the next step to tart them up - sour, citrus, caramelised, brown sugar, bitter might become “Oxford marmalade” - something that can try and scattershot hit a few perceived flavours while sounding quite nice. Something that will sell you the coffee

Eventually it’s time - time to release the coffee to the world. Depending on your supply chain flexibility and waste tolerances, you may be able to do a test roast and then print final bag labels/supplementary marketing materials with amended notes. Or perhaps you have a lead time that makes that impossible. In any case, we put the coffee in the production roaster and do the first roast(s) - and we might find a bit of a different expression than we thought!

Maybe the sample roast tasted like marmalade, but we absolutely nailed the production roast and it tastes clearly and cleanly like fresh mandarin wedges. Broad scopes - still citrus, still in that orangey flavour vibe, but different than what we said. Do we alter the roast to make the tasting notes more accurate? Or do we accept the difference because we like our work on the roasting?

Should we throw away pre-printed labels, or re-do our copy because we found the coffee could taste different and we liked it? Do we go to the effort and waste?

Or do we make it the end consumer’s problem and move on. I invite the reader to consider the most likely solution chosen.

Because we hit the other big problem - coffee is an unfinished product. That coffee in the lab might be ground on an EK43 grinder, cupped and brewed with reverse osmosis water. Maybe there’s not a huge amount of time to brew it again and really dial in. Equally, maybe you’re at home with the best grinder you could personally afford - which works for you, but it’s no £3000 professional giant hunk of metal taking up half your countertop, or you had a cafe grind it for you, so things are fading a bit. And you’re brewing with a cartridge jug or other water. Or you have the most amazing home setup, better than a QC lab (especially because you have the luxury of time), you make your own water, you sift fines, have the latest and best filters, brewers, youtube recipes…

In every single case, that very same roast of coffee can taste wildly different. Perhaps all within the same broad strokes, but the specifics are going to change.

So we have a conundrum - specific, fancy tasting notes sell coffee. But specific, fancy tasting notes are situation specific. If I sell you a coffee and tell you it’ll taste like ripe yellow passionfruit, and all you can taste is cheesy fermentation and a sour acidity that could be somewhat tropical - then to my mind, we have an issue. As a roaster I could just use the cop out - you’re not brewing it right, must be the water, the grinder, etc…

And now we have the final problem. We’ve discussed fresh coffee so far - but what happens when we as a roastery buy too much? What we call having a “long position” (ie - we are holding too much stock, it will last for a long time).

Either that means our lovely fresh crop coffees will sit waiting for a space to open up to release for sale, or perhaps in the case we overbought this specific coffee, it might mean it hangs around too long. So both examples of how a coffee might be released with flavours that aren’t accurate anymore, or how it might change over the period of months if it’s on too long.

A coffee that starts to fade and show age flavours, invariably needs to be roasted darker - if even a little bit. As roasters we can only add flavours of roast, and so as the coffee loses some of the brighter, vibrant notes, we might want to make it taste more caramelised, more cooked, as a replacement - changing the expression to one more suited to the current state of affairs.

But it’s an uncomfortable truth - do you admit your coffee has gone stale, and re-release it as a darker roast? Are your systems even set up to do that? Or do you keep up the pretence that it still tastes like it landed, and keep the same flavour descriptors? After all, you need to sell it, and it’s sitting around too long…

This happens far, far more often than people like to admit.

So this has been long, but I think there’s a point I’m driving at. How useful are a lot of the tasting notes you’re going to encounter? And in my mind, the answer is - probably not as much as we’d like.

Personal perceived preferences, Tasting with others, sharing what you commonly perceive - massively useful. Marketing taste notes to sell you a coffee? Not as much, or, they should be taken with a huge pinch of salt. It’s so personal that anyone can be a bit deceptive and you have little scope to catch it. We also assumed that every batch will be perfect - although roastery consistency has gotten amazingly good, it’s still possible to have off-profile batches. These will either get blended back, or sent anyway - because with rare exceptions, wasting hundreds of pounds of coffee that probably tastes close enough to intended isn’t what most roasteries fancy doing on a regular basis.

Image - the SCA flavour wheel, reproduced with permission.

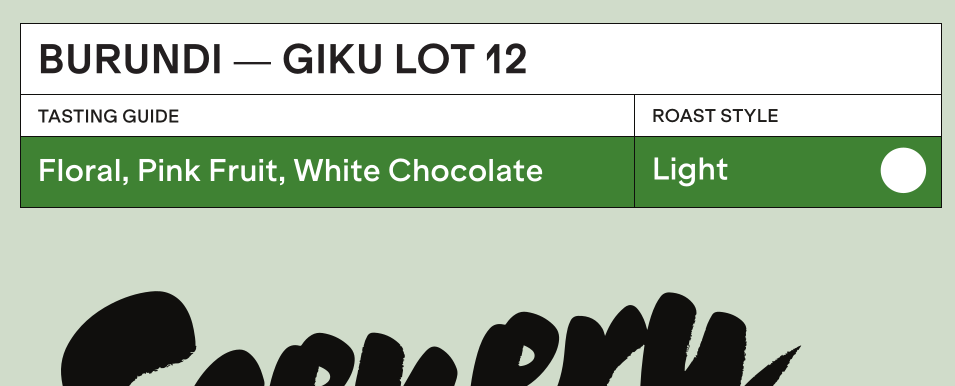

Our answer to tasting notes is to give a tasting “guide” - based on the SCA flavour wheel, which has standard references for the perceived flavours and is backed up with sensory research. We aim to be within the inner, simpler wheels of the flavour wheel, giving a general idea of the flavours you will find, which we are confident will be representative over a wide range of scenarios - but allowing and encouraging for more personal perceived taste experience. We are not dictating what you must find in your coffee - we encourage exploration.

We are being strict with ourselves - we don’t tell you what a coffee tastes like, only what we experience when we’re brewing and tasting it with our setup. That means we are eschewing some of the marketing and sales boosts that these types of tasting notes give - it may well be an unsustainable business decision, our coffees just might not sell compared to those willing to play the game. But we’d like to try doing something a little different, a little more straightforward, and a little more honest. We really, really want people to tell us what the coffee tastes like to them, far more than what we think it tastes like - because that’s a truly special thing. To know we helped someone taste something and it reminded them of a flavour, an experience in their past - that is an incredibly gratifying feeling as a coffee professional.

Your brewing and tasting experience is valid.