Let’s face it - I thought this would be a quick addition to the posts I had already written, something I could knock out in a week and keep the posts rolling. But emphatically - it is a topic that is too big and too complex for me to condense - and I also found myself exposing my own gaps in knowledge in the process.

It’s time to swallow the frog and write the post - but not the one I originally intended. I bit off more than I could chew - tried to condense a field that people specialise in and make careers out of, but I merely interact with it. A secondary key piece that has helped me unblock this post is discussing the content with Mat North - feeding back that perhaps I shouldn't put words in the mouths of others, an easy trap for a roastery green buyer to fall into.

To bait and switch - this post can’t be about risk. There’s too much to talk about that and freshness - even a brief look at every step of the chain yields a daunting number of complex risk factors: weather, global economic instability, currency volatility, changing demand patterns, among many others, are all topics that both take a lifetime to master and deserve separate full posts of their own. So let’s tackle the second part of the topic:

The ticking clock of freshness:

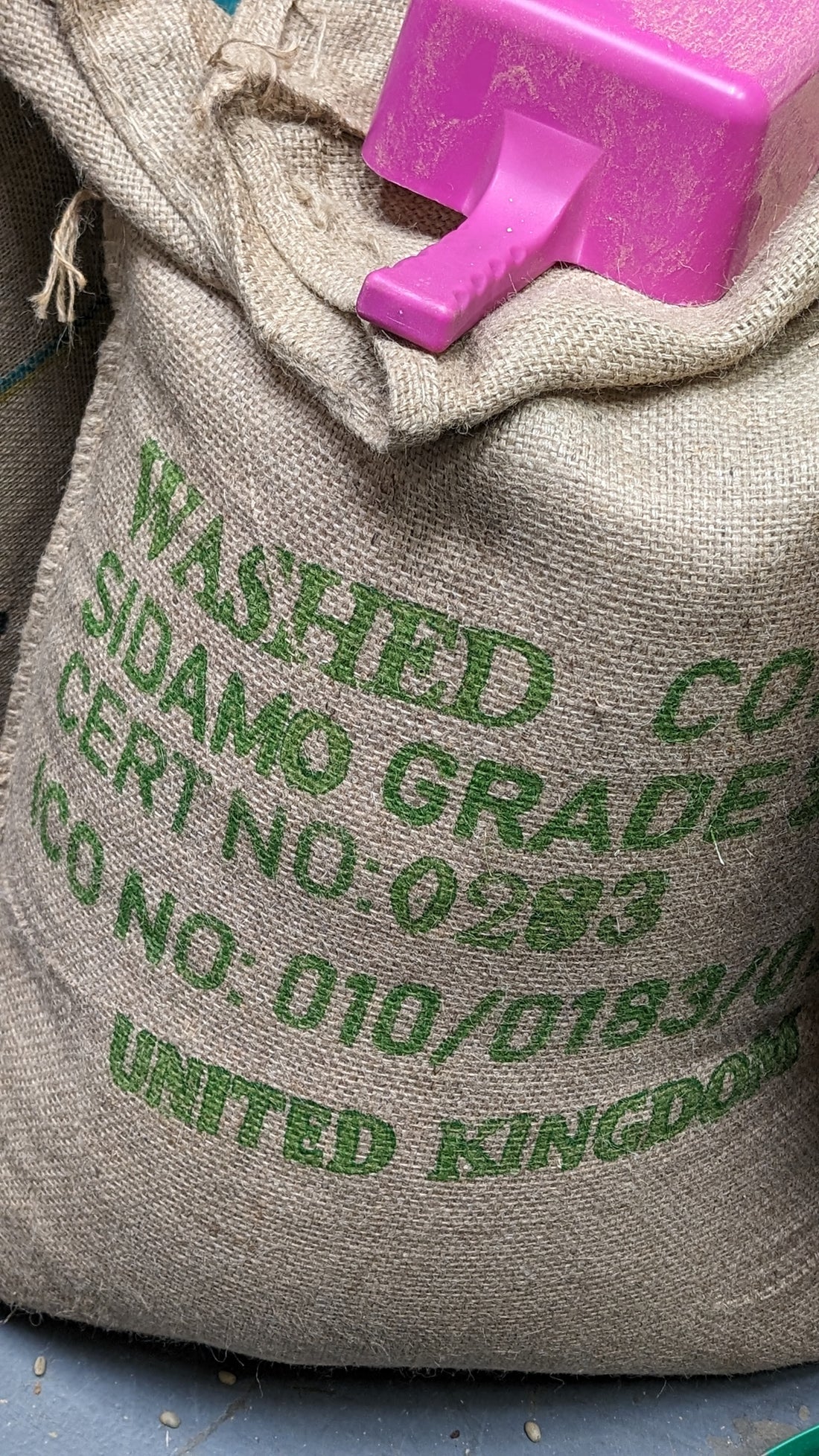

Green coffee is not a shelf stable product. Coffee is the seed of a fruit, produced from a harvest season, and depending on the quality of the processing and drying process, will maintain a certain period of peak quality before starting to deteriorate. This is true across all grades of coffee - even for the lowest grades of commercial coffee; but it is especially important for speciality. Speciality coffee has distinctive characteristics, and the flavour of age (papery, oxidised, woody, jute fibre) is considered a negative attribute. You can freeze green coffee to prevent staling, however that comes with a significant energy cost associated that only makes sense for the most premium crops - so in general, the longer coffee sits in a warehouse, the more it will travel through its arc of quality - moving from fresh, tight flavours, to a peak of expression, to fading vibrancy, till finally the dreaded age flavours become present.

Thus, when we deal with the risk and the structure of the supply chain, we must always contend with the ticking clock of freshness - the pressure to process, to move coffee, to sell it, to sell it again, perhaps a third time still as it moves through the logistic intermediaries, to roast it, to sell that roasted coffee, and finally as an end consumer to grind and brew your coffee whilst it still holds the maximum value. At several key points in the process, the “time on the clock” is changed - either adding or subtracting.

When coffee is picked off the tree as a fresh fruit, we are talking a matter of hours to a day at most before it starts to rot unless the processing is started. When coffee is dried to be shelf stable, depending on the quality of the drying process, it could be months or even over a year before age starts to creep in. When we roast it, we reset the clock - we find our coffee lasts around 3 months in a sealed bag, with peak flavour around the 3-6 week mark. Grinding it takes us down to a short few days, and most brews are stale after an hour. The clock ticks ever onwards at every stage.

It’s worth mentioning that on roast freshness - that we emphatically do not believe in the concept of “roast to order” - we roast fixed batch sizes because the quality and consistency of the roasting is significantly higher, when compared with an approach that changes the batch size to suit order volumes with every single roast day.

That means, necessarily there will be some overage roast day to roast day. Since we know our coffees stand to taste better with rest, we keep any unbagged stocks sealed in food-safe bags in buckets, tied off with minimal headspace - reducing oxidation. Speciality coffee is trapped in a monster of its own marketing creation, where the expectation we created that coffee must be bought a day off roast and consumed within 2 weeks (back when the need to differentiate from commercial coffee and most roasts were darker) prevents most people from enjoying truly vibrant, lighter roasts at the time they are peaking in quality.

But I digress!

The race against the clock - forecasting:

Very rarely is a sack of coffee pre-sold down to the final retail bags - so from the farmer through to the roaster, there is an amount of forecasting going on - thinking purely about volumes here -

A producer might ask:

What is a viable amount of coffee to grow to gain a living income? What will the demand be? How much labour and agrochemical inputs will it require to manage the harvest, how much capacity do I or my local mill have to process

Exporters and importers might ask:

What is the market looking like - both in supply and demand? How are logistics looking - are there delays, is it easy to move coffee? How much coffee should we bring in to a certain market? How much is already pre-sold and committed to buyers?

A roaster might ask:What are my current volumes and needs? What do I expect to see in growth? What do my customers want? When will I finish my current stocks, and how long will this purchase last for?

Over purchasing coffee - sitting on more than you can reasonably use or sell in a given time period - is broadly going to mean that coffee will start to fade and lose value once the ticking clock of freshness counts down to near zero. And we run into a conundrum - what do you do when your microlots are baggy, your blenders no longer speciality grade, your premium top end hype lot no longer on top?

Do you take the hit, pull it from sale - find an alternative channel, or take the hit on your costings by blending it through something else? Do you claim it still has the same value even when it’s clearly degraded (although it still holds some form of value, just a different one to the original proposition)? Do you sell it at a discount?

The last point is particularly important for coffee bought for the spot market - off the shelf available in the country of consumption. Remember that both importers and roasters will always be forecasting - contracting up to and over a year in advance or working 6 months ahead, whilst coffee might be on the trees or on the beds and well in advance of it leaving the port of origin.

Coffee sitting in a warehouse is typically racking up two crucial things - finance costs (if the money to import has been loaned) and warehouse rent. In some occasions where the position is too long, the warehouse too full, there may not even be the space to add more coffee from fresh landings until some of the older stock is moved on. The paradox is - the longer it sits in a warehouse, the less it’s worth, but the more it costs. The pressure ratchets up.

A producer was still paid properly for their harvest, even if their coffee remains unsold at the final point in the chain (naturally there will be some terrible exceptions to this, but it broadly remains true) - and a roastery can make use of this to purchase coffee at a discounted price from an importer, where the importers margins are the ones affected by the loss. But it is a false economy to think this is the way out of the “cheap, high quality, ethical” trilemma - because that loss will oft translate to downwards pressure come the next harvest. Either the demand will be lower and the producer may struggle to sell as much, as they are seen as a risk, or perhaps the price offered will be lower too, or both. The ticking clock puts the pressure on - no matter where you are in the chain.

Weird paradoxes can start to occur - where speciality importers are long due to over-forecasting or reduced demand, implying that prices should reduce to meet market needs - but commercial coffee futures exchanges are short (due to regulation changes) - keeping prices high. Good for the producers, terrible for importers looking to remain viable. Price reducing pressure always moves upstream.

Purists demand or imply that is viable to cut-loose on ageing coffee (including one rather “famous” coffee influencer who proposed to ignore all east african coffee in late winter, right when fresh crops from Rwanda and Burundi are landing) - they are actively harmful to an equitable supply chain.

Cynics sell it anyway and assume nobody will care. I look forward to integrating these coffees - that still hold a form of value, just not the originally proposed one - in a transparent way. We’ve started listing the harvest dates and arrival times of our coffees on our website and will phase in any that are not currently listed as the components change - with the intention that as and when we purchase lots that have been well processed and dried, that are outside of their typical seasonal window and are holding up well - that we will be just as transparent as when something has arrived straight off the port and into the offer.